A million dollar challenge to break the ancient Indian script

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEvery week, Rajesh PN Rao, a computer scientist, receives emails from people claiming to have cracked an ancient script that has baffled scholars for generations.

These self-proclaimed codebreakers – from engineers and IT workers to pensioners and tax officers – are mostly non-Indians or natives of India. All of the Indus Valley Civilizations are convinced that they deciphered a mixed script of signs and symbols.

“They say we solved it and it’s case closed,” said Mr. Rao, the Huang Endowed Professor at the University of Washington and author of peer-reviewed studies on the Indus script.

Adding fuel to the competition, MK Stalin, the Chief Minister of the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, recently announced that he will raise the competition and offer a $1 million reward to anyone who can crack the code.

The Indus or Harappan civilization – one of the world’s earliest urban societies – emerged 5,300 years ago in what is now northwestern India and Pakistan. Its hardy farmers and merchants have prospered for centuries, living in walled and bricked cities. Since its discovery a century ago, nearly 2,000 sites have been discovered in the region.

The causes of the society’s sudden collapse are unclear, with no evidence of war, famine or natural disaster. But the biggest secret is that the script has not been copied, leaving its language, administration and beliefs a mystery.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor more than a hundred years, experts – linguists, scientists and archaeologists – have tried to decipher the Indus script. Theories have already linked it. Brahmi scriptsDravidian and Indo-Aryan languages; SumerianAnd he even said it was made with political or religious symbols.

However, the secrets remain locked away. “The Indus script is probably the most important writing system,” says Indologist Asko Parpola.

These days, the more popular mystical theories equate the script with the content of Hindu scriptures and attribute spiritual and magical meanings to the texts.

Most of these tests ignore the fact that a script made of signs and symbols appears mostly on stone seals used for trade and commerce, making it unlikely that they contain religious or mythological content, Mr. Rao said.

There are many challenges to deciphering the Indus script.

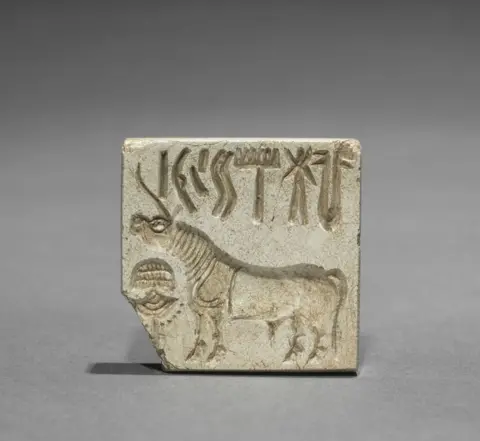

First, the relatively small number of scripts – about 4,000 of them, almost all on small objects such as seals, pottery and tablets.

Then the brevity of each script – about five signs or symbols – the average length – there are no long inscriptions on walls, tablets or vertical stone slabs.

Consider the commonly found square stamps: lines of symbols run across them, with a central animal motif – often a unicorn – and something beside it, the meaning of which is unknown.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere is no bilingual art like it. Rosetta stonewhich helped scholars decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs. Such artifacts contain text in two languages, which provides a direct comparison between known and unknown script.

Recent advances in deciphering the Indus Script have used computer science to solve this ancient puzzle. Researchers used machine learning techniques to analyze the script, trying to identify patterns and structures that could lead to understanding.

Nisha Yadav, a researcher at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) in Mumbai, is one of them. In collaboration with scientists like Mr. Rao, her work focused on applying statistical and computational methods to analyze the undeciphered script.

Using a digital dataset of Indus symbols extracted from the script, they found interesting patterns. Note: “We still don’t know whether the signs are complete words, or parts of words or parts of sentences,” says Ms Yadav.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMs Yadav and co-researchers found 67 symbols covering 80% of what was written on the script. A two-handled pot-shaped symbol was found to be the most commonly used symbol. Also, the scripts started with many symbols and ended with few. Some symptom patterns are more common than expected.

Also, a machine learning model of the script was developed, paving the way for further research, to restore illegible and damaged text.

“Our understanding is that the script is structured and that there is an underlying logic to the script,” she says.

To be sure, there are many ancient texts that are unexplained, facing similar challenges to the Indus script.

Mr. Rao mentioned such scripts Proto-Elamite (Iran) Linear A (Crete) and Etruscan (Italian), whose root language is unknown.

Others, like News (East Island) and Zapotec (Mexico), have recognizable languages, “but their signs are not clear.” The Phaistos Disc from Crete – a mysterious, burnt clay disc from the Minoan civilization – “closely depicts the challenges of the Indus script – the language is unknown and there is only one known example.”

Getty Images

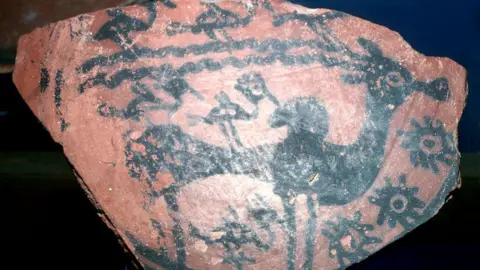

Getty ImagesBack in India, it is not entirely clear why Tamil Nadu’s Mr. Stalin announced an award for solving the script. His announcement followed new research linking Indus Valley symbols to graffiti found in the state.

K Rajan and R Sivananthan analyzed more than 14,000 graffiti-bearing pottery fragments from 140 excavated sites in Tamil Nadu, which included more than 2,000 symbols. Most of these symbols are similar to symbols in the Indus script, 60% of the symbols are related, and more than 90% of South Indian graffiti symbols are similar to the Indus civilization, the researchers say.

This “suggests some kind of cultural contact” between the Indus Valley and South India, say Mr Rajan and Mr Sivanathan.

The move by many to announce Mr. Stalin’s award has cast him as a staunch champion of Tamil heritage and culture in defiance of Narendra Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in Delhi.

But pundits are confident that there will be no claimants to Mr. Stalin’s prize any time soon. Scholars have compiled complete, updated databases of all known artefacts – critical to deciphering them. “But what did the Indus people write? I would love to know,” says Ms. Yadav.