A23a: A giant iceberg on a collision course with an island

Climate and science reporter

Data journalist

Getty Images

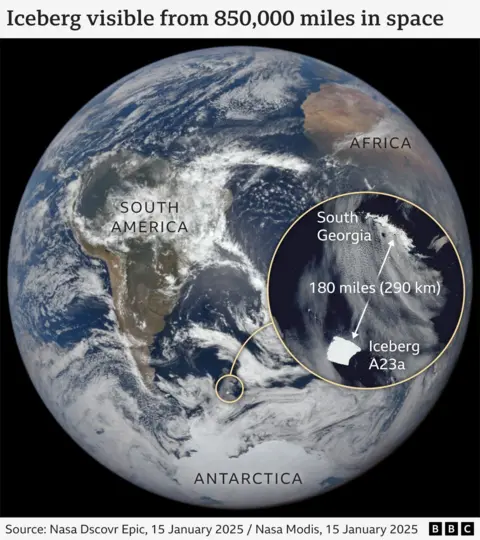

Getty ImagesThe world’s largest glacier is on a collision course with a remote British island, threatening penguins and seals.

Glaciers are drifting from Antarctica into South Georgia, a rugged British territory and wildlife refuge, potentially cutting and breaking land. It is currently 173 miles (280 km) away.

Countless birds and seals died on the frozen shores and beaches of South Georgia.

“Icebergs are dangerous by nature. I would be very happy if we missed them completely,” sea captain Simon Wallace told the BBC.

BFSAI

BFSAIScientists, sailors and fishermen around the world anxiously scan satellite images to track the daily movements of this iceberg queen.

is it. It is known as A23a And it is one of the oldest in the world.

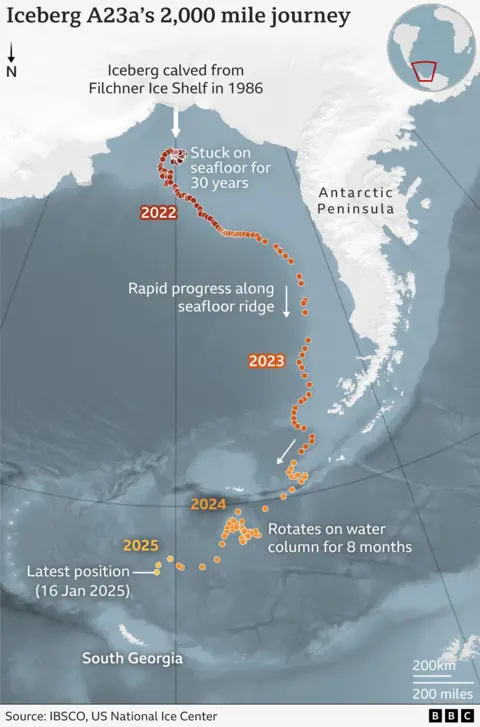

In the year In 1986, it was born or separated from the Filchner Ice Shelf in Antarctica, but stuck to the sea floor and then became trapped in an oceanic gyre.

Finally, she was freed in December and is now on her final journey, speeding towards oblivion.

Warm waters north of Antarctica are melting and undermining giant cliffs up to 1,312 feet (400 meters) high, taller than the Shard of London.

It once measured 3,900 square kilometers, but the latest satellite images show that it is slowly decaying. It is now about 3,500 square km, roughly in the English county of Cornwall.

And large pieces of ice are breaking off, they are entering the water around the edge.

A23a could enter large sections any day, which could last for years, like the uncontrolled drifting of icebergs around South Georgia.

This is not the first giant glacier to threaten South Georgia and the Sandwich Islands.

In the year In 2004, the so-called A38 spread across the continental shelf, leaving dead penguin chicks and chicks on beaches as massive icebergs cut off their feeding grounds.

The territory is home to majestic colonies of emperor penguins and millions of elephants and fur seals.

“South Georgia sits on an ice sheet, so impacts to both fisheries and wildlife are expected, and both have the ability to adapt,” said Mark Belchier, a marine ecologist who advises the state of South Georgia.

Sailors and fishermen say ice is a growing problem. In the year In 2023, a man named A76 gives them a scare as he approaches the ground.

Mr. Belchier, who saw the glacier while at sea, said: “The pieces of it were rising, so that they looked like great towers of ice, a city of ice on the horizon.”

Those tiles can still be found around the islands today.

“It’s the size of a lot of Wembley stadiums, down to the size of your table,” says Andrew Newman of Argos Fries, a fishing company based in South Georgia.

“These pieces basically cover the island – we have to work through it,” said Captain Wallace.

The crew on board must be constantly alert. “We have searchlights all night trying to see the snow – it can’t come from anywhere,” he explains.

The A76 was a “game changer” according to Mr Newman who had “a huge impact on our operations and the safety of our ships and crew”.

Simon Wallace

Simon WallaceAll three describe a rapidly changing environment, year-to-year ice retreat, and variable sea ice levels.

Climate change cannot be behind the birth of A23a because it was born long ago, before most of the warming effects we are seeing now.

But giant glaciers are part of our future. As Antarctica becomes more unstable with warmer oceans and air temperatures, more ice sheet fragments accumulate.

Before the end of time, however, A23a left a parting gift for scientists.

A team from the British Antarctic Survey on Sir David Attenborough’s research vessel Closer to A23a in 2023.

The scientists seized the rare opportunity to investigate what the mega-glacier would do to the environment.

Tony Jolliffe/BBC

Tony Jolliffe/BBCThe ship entered a crevasse in the giant walls of the ice and PhD researcher Laura Taylor collected precious water samples 400m from the cliff.

“I saw a huge wall of ice towering above me. It was different colors in different places. Pieces were falling off – it was great,” she said from her lab in Cambridge. By analyzing the samples.

Her work looks at the effects of meltwater on the carbon cycle in the Southern Ocean.

Getty Images

Getty Images“It’s not just like drinking water. It’s full of nutrients and chemicals, and tiny animals like phytoplankton are frozen in it,” Ms. Taylor said.

When glaciers melt, they release those elements into the water, changing the physics and chemistry of the ocean.

That can store more carbon in the ocean, as particles sink from land. That would naturally lock in some of the planet’s carbon dioxide emissions, which contribute to climate change.

Icebergs are incredibly unpredictable and no one knows exactly what they will do next.

But soon a behemoth must appear, looming over the horizon of the islands, as large as his empire.